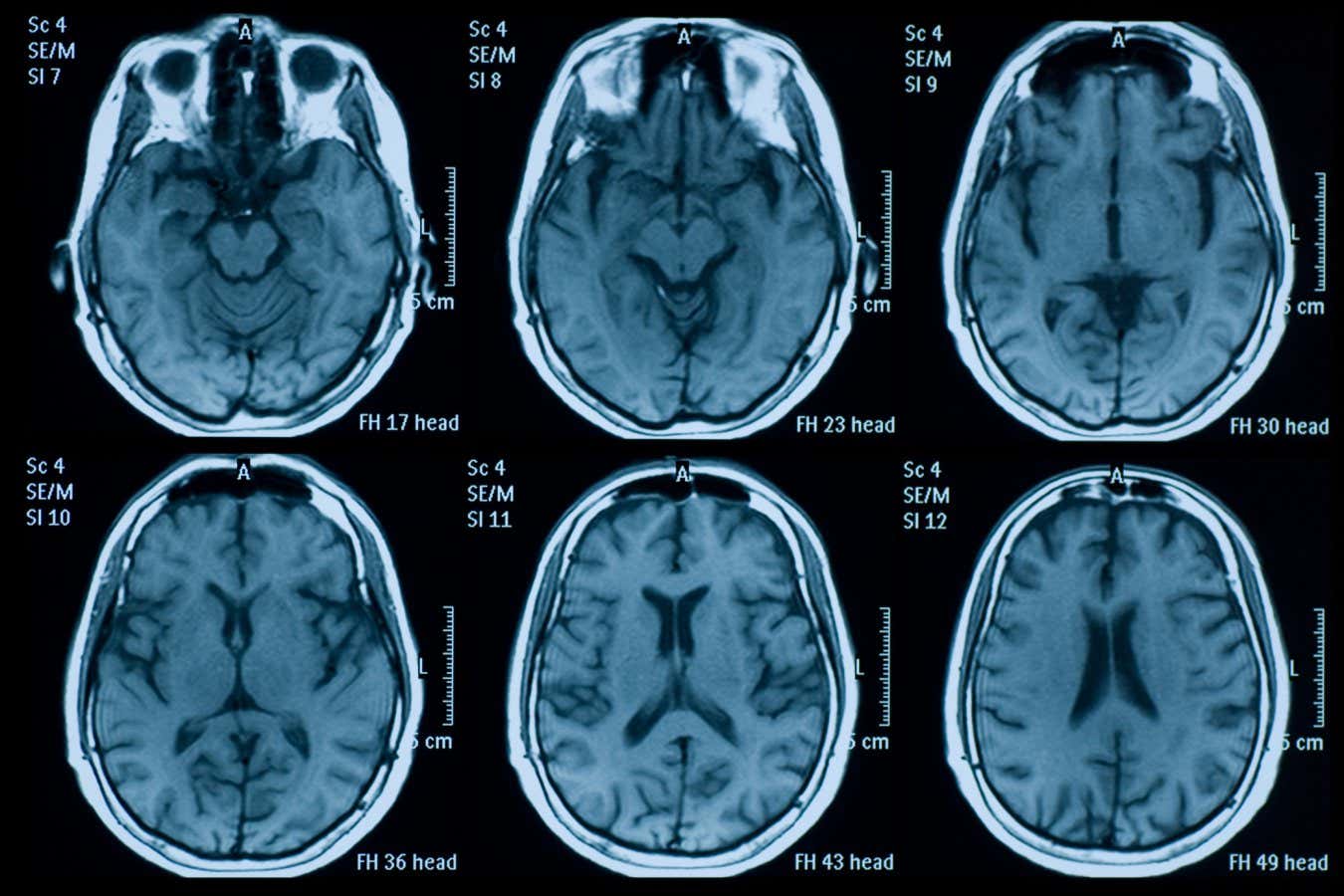

Structures within the brain change over time Temet/Getty Images

The covid-19 pandemic may have accelerated the ageing of our brains even before we caught the infection. Research suggests that even relatively early on in the outbreak, brains aged by 5.5 months, possibly due to stress or lifestyle changes.

We know that many people with long covid experience brain fog, but years after the arrival of covid-19, the pandemic’s broader neurological impact is far from fully understood.

Advertisement

To get a grasp on this, Ali-Reza Mohammadi-Nejad at Nottingham University, UK, and his colleagues trained a machine learning model on 15,000 brain scans to identify how its structure changes with age.

They then fed the model pairs of brain scans from 996 volunteers from the UK Biobank study. Of these, 564 had both scans taken before March 2020, when lockdown was introduced in the UK, and acted as the control group. The remaining 432 volunteers had one scan before March 2020 and one later on. Each scan was three years apart, on average, with a minimum gap of two years.

When the researchers compared individuals from the two groups – who were matched for age, sex and overall health – they found that the pandemic may have accelerated the ageing of our brains by 5.5 months, based on structural changes to white and grey matter. This was true even among those without a known covid-19 infection, which was recorded as part of the Biobank project.

Free newsletter

Sign up to Health Check

Expert insight and news on scientific developments in health, nutrition and fitness, every Saturday.

This accelerated ageing was particularly pronounced among men and those who were more socioeconomically deprived. But Biobank participants are generally healthier, wealthier and less ethnically diverse than the rest of the UK, so the findings may not apply more broadly.

The researchers speculate that these changes may have come about due to loneliness or stress of lockdowns, or lifestyle shifts that may have occurred around that time, such as with exercise levels or alcohol consumption.

They write in their paper that the structural brain changes could be “at least partially reversible” and point out that the findings are limited by the fact that the participants were all from the UK, so the results may not reflect the potential effects of lockdowns elsewhere. “Our findings may actually underestimate the impact of the pandemic on more vulnerable populations,” says Mohammadi-Nejad.

Journal reference:

Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61033-4

Topics: